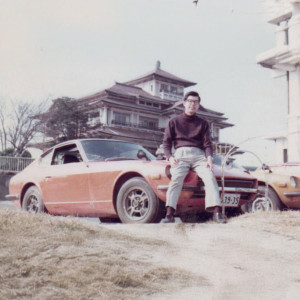

He was closely involved in the development of the Nissan Fairlady Z, which we know outside of Japan as the Datsun 240Z. Now, at 81, Takeo Miyazaki is the only one who can still talk about it from personal experience. He had to solve many problems to turn the Z into a jewel, but he enjoyed it every day. “It was the most beautiful and most intensive period of my life.”

Takeo Miyazaki, on the twisty road to the perfect sports car

Original article: Octane NL magazine 12/24

He had actually been interested in the Prince Motor Company, and had set his sights on it as a young man. “I really wanted to be part of the creativity, camaraderie and drive at that manufacturer. When I went there for a job, I asked if I could speak to the boss, but he was nowhere to be found, at least not in his office. I found him in the factory, on his knees, bent over a box of pistons. That was so typical of the hands-on atmosphere at Prince,” Takeo Miyazaki recalls. He did not work for PMC for long, because the company was taken over by the Nissan Motor Company, but there he was faced with an enviable challenge: the development of the S30, also known as the Nissan Fairlady Z and Datsun 240Z.

We meet Takeo Miyazaki in Buren, at the Visscher Museum, where he has graced the opening of S30.World, a unique tribute to the Datsun 240Z (and Nissan Fairlady Z), and not only that. He spent an intensive day there filming to tell his unique story on the S30.World website.

Miyazaki was born in 1943 in Osaka, and the automotive industry was not his destiny. His father had a different future in mind for him. The man owned a clothing company and in his eyes his two sons would continue the business. The youngest, Takeo, was to study chemical engineering at Kansai University to learn how to invent new methods of coloring fabrics. His heart, however, lay elsewhere. He was a car guy from the start, driving a succession of Hillman Minx convertibles, Prince Skyline 1500s and Nissan Fairlady 1500s.

Miyazaki looks back: “Those eight years at university were a period of freedom, which I enjoyed as much as possible, including racing the Honda S800. There was a special brand cup for this at Suzuka, with 24 cars. More or less professional drivers with factory support were at the forefront. I dare say that I was one of the better private drivers. During a rain race, a number of top drivers crashed and I came in fifth. I then received an offer to drive for a professional team because I was fast and knew how to keep the car in one piece. But I didn't accept, my interest in racing was waning by then. My father had passed away, I no longer had to work in his company and I could do whatever I wanted, which was to choose between the automotive industry or an airline.”

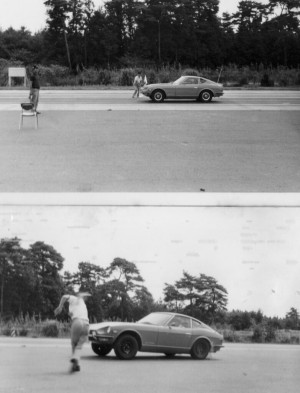

“The car was not allowed outside during the day, and we did dynamic tests at night on our test track.”

The automotive world held the strongest appeal. After the takeover of Prince, Takeo Miyazaki was incorporated into the Nissan Motor Company and a task awaited him that would characterize his entire life. The design of the Datsun 240Z and Nissan Fairlady Z, together referred to internally as the S30, had already been established, but the car had yet to be fully developed – and properly developed at that. Nissan had already introduced a sporty open car to the market, the Datsun Sports (called the 'Fairlady' in Australia and the USA), but wanted to take the world stage with a serious, competitive sports car. Miyazaki: “It had to be better than the MG B that was so popular in the USA and could not be more than $200 more expensive. I was a rookie and was appointed to the team that was to develop the S30, much to my delight and surprise. That was very unusual and all my colleagues envied me. I knew far too little to be able to handle the task, but I was determined to make the S30 the best car possible.”

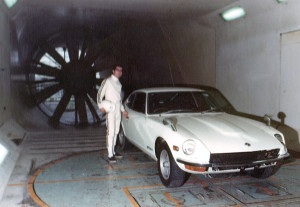

“One of my first tasks was to re-test everything that the other teams had already done. I found that a strange assignment because all those teams, which consisted of very competent people, had already carried out those tests. At first, I didn't quite understand that double-checking, and it only happened with the S30. When the first complete prototypes were not yet ready, I had time to gather as much knowledge as possible. As far as driving characteristics are concerned, I learned a lot from my boss, Mr. Kamata, who was incredibly sensitive when it came to the road behavior of a car. Hideyuki Sakamoto introduced me to the air currents around a scale model of the S30 in the wind tunnel at the University of Tokyo, and Mr. Sakata, who was responsible for the race cars at the Prince Motor Company, taught me about the heat management under the hood. I was lucky to have had the opportunity to learn from such highly skilled people.”

“I needed all the teams to help me and to teach me how to test and assess a prototype. They were all willing to do it, just for one day. They were hesitant at first, but when they heard it was for the S30, they were ready to go and I got the very best people. I only had two weeks to acquire the necessary knowledge and worked six days a week, day and night. During the day we tested the engine, the rigidity of the body, the suspension, the handling and so on. The car was not allowed outside during the day and we did dynamic tests at night on our test track.”

During one such nocturnal dynamic test with an S30, a shocking discovery was made. The car had not been camouflaged to eliminate the influence of the 'packaging' on weight distribution and aerodynamics. Miyazaki: “To drive the super-secret S30Z ‘naked’, all the lights on the test track had to be off and there were ten guards along the track to prevent any curious onlookers. There was a small hill with an observation platform and there was also a guard watching from there. My boss, Mr. Kamata, and I only had 30 minutes of track time. We set off around midnight. I had just told my boss that I had racing experience, but he took the wheel and we drove off. Time was precious. Mr. Kamata drove the road course twice, then the handling course, and when he had done that twice too, he scratched his head, zigzagged 500 meters and drove to the skid pad. He shouted that I should hold on tight and drove four laps, two clockwise and two counterclockwise. Then I had to drive, zigzagging, as fast as possible. He wanted to hear the tires squeal.

Afterwards he asked what I thought. I said that I felt that the car was less stable when we drove counterclockwise, but I couldn't answer his question as to 'why'. During the tests, we hadn't noticed that difference because we always drove counterclockwise on our circuits. Mr. Kamata immediately stopped the session, even though we had 20 minutes left. He said there was no point in continuing. I was almost in a panic, especially because I didn't know the answer to his question.”

Of course Kamata knew the answer himself, the spring constants of the four coil springs differed – a lot. Of course they should have been checked beforehand, on all prototypes, but that had not been done. He turned a blind eye because a new team without experienced experts had been put in charge of the handling and he ordered everything to be redone – with springs exactly within specifications. He also said he wanted to repeat the tests himself, together with Takeo Miyazaki, because it had been a long time since he had driven with someone who knew how to find the gas pedal so well, he said.

Takeo: “I was overjoyed by those words, they instantly lifted me out of my depression after this debacle. I was even more impressed by Mr. K. than I already was. In a few seconds he had noticed the imperfections of the S30. I had already heard what he was capable of, but this exceeded all my expectations. He was the best of the best, a first-class professional, and after experiencing this with him, I was completely convinced that the S30 would be a perfect car. With a man like Mr. Kamata at the helm, it couldn't be any other way.”

Miyazaki immediately contacted Nippon Hatsujō Kabushiki in Yokohama, the company that produced the springs, and ordered ten front and ten rear springs. “Someone from our Performance Group taught me how to measure the spring constants, which I then did with all twenty. Of the ten front springs, only four met our specifications, and of the rear springs, only three. The chance that we had tested correctly was less than 50%.”

The cause of this was a lack of knowledge at NHK. The company already had a lot of experience with leaf springs, but not with coil springs.

“It was assumed that they would all have approximately the same spring constant after heating, but that was far from the case,” says Miyazaki. “NHK then started testing them before delivery to give us the right specifications, which took three minutes per spring. We also started measuring the springs ourselves in all our tests with the prototypes, which took us an hour per car, but without knowing for sure that we had the right springs, there was no point in testing.”

The S30 was developed in an incredibly short period of two years, and for the Nissan Motor Company it was an entry into a completely new segment. That it was an instant hit is nothing less than a tour de force, for which a lot of hard work was done. Literally everything had to be newly designed, developed and tested: the position of the aerodynamic pressure point in relation to the center of gravity, the tuning of the wheel geometry, the springs and dampers, the thickness of the stabilizer bar, the behavior in the wind tunnel, the choice of tires, the ergonomics, the weight of the steering, the cooling and air currents under the hood, an almost endless list. Even relatively trivial problems had to be solved, such as the problem of ash flying away when a cigarette was placed on the ashtray.

As we take a drive with some 240Zs from the collection of our host Chris Visscher – initiator of S30.World – we see a smile appear more and more often on the face of the initially somewhat reserved Miyazaki. It is clear that the car triggers emotions in him – strong emotions, because it has been thirty years since he last drove an S30. After the car was ready for the outside world, he was promoted, which he was not very happy about in his heart. “I mainly had office work and that was much less fun than rolling up my sleeves for the S30.”

“We were all car enthusiasts and regularly bought German and English magazines, which we had a pool for among ourselves.”

Those hands of his have spent an incredibly long time on the wheel of an S30 in a short space of time. “In the space of four months, we did a 50,000 kilometer high-speed test with two S30s. That was in December 1969, shortly after it was officially announced. We left our test center in Yokosuka at eight in the morning and drove along the Tomei Expressway to the airport near Hamatsu and turned around there. We had to be back by five at the latest to carry out a final inspection so that the night shift could leave at eight. That meant we had to average about 140 km/h. There were still few trucks on the Tomei Expressway at the time, and we could easily reach 160 km/h. The police at the time drove Toyota Cedrics and Crowns, usually around 120 km/h, and we saw them before they saw us. If I came across a police car and had to slow down, I skipped my lunch break, which is why I always had a piece of bread in my pocket.”

Miyazaki continues: “When the prototype of the S30 was finished, our full-scale wind tunnel was not yet ready, but we were convinced that the car would stick to the road due to its design. We didn't know for sure because we had only tested on nice days, without crosswinds, and not above 140 km/h, because that was the maximum speed on our Oppama Test Course. The team that tested the S30 on public roads had also said that the stability was good, and we all had complete faith in it. But when we were able to use the large wind tunnel, the air resistance turned out to be greater than we thought and the S30 experienced 25 millimeters of lift at the front and 15 millimeters at the rear at 120 km/h. By modifying the suspension, we were able to reduce that to 20 and 10 millimeters, which was comparable to the Bluebird, Skyline, Porsche, Jaguar and Corona that we had also tested.”

It was clear that spoilers were needed – and they were fitted to the 240Z fairly quickly. The first thing that was thought of was a front spoiler with an 'overbite', which made a 45-degree angle under the nose of the car, where the force of the airstream would cause a downward force. Takeo: “We were all car enthusiasts and regularly bought German and English magazines with our pocket money, we had a pool for that. To our surprise, we saw a photo of a Porsche that had won a race with a vertical spoiler at the front. At first we didn't understand how it could cause downward pressure. We had a 911, which we had purchased for comparison tests, and we started experimenting with it. A vertical spoiler appeared to have the same effect as a slanted spoiler because the airflow under the car was restricted and lower pressure was created there – and there were hardly any adverse effects on the drag.

The same thing turned out to be true for the S30. There was hardly any difference between the two types of spoilers in terms of air resistance, but with the vertical one we had more pressure on the nose and also on the rear spoiler. Moreover, we still had ample ground clearance, which is why we chose the vertical one. It also fit much better with the design of the car.

However, stability at high speeds had to be improved beyond what spoilers alone could achieve. What turned out to have a major influence on the aerodynamic properties at high speeds was the air that flowed into the engine compartment through the grille, which caused significant upward pressure under the hood. Miyazaki: “Another factor at the time was that marketing wanted the S30 to be the first Japanese car with a Cw value of 0.4. I didn't see the value in that because the Cw does not say everything about the smoothness of the body. The thickness of the radiator, the changing position of the car at speed and the weight of the engine, for example, are also factors that influence the Cw. But the car magazines were very excited about it, and we understood its importance in confirming the S30's characteristics as a sports car. It was an obvious choice to cover the headlights with transparent covers, which gave us 0.398 compared to a car without spoilers. But those covers were an extra, and I wanted to achieve that 0.4 without them.”

“When the normal working day was over, I clocked out so as not to anger the union, and then quietly went back to work”

That this required modifications under the hood had long been clear to Miyazaki. “There was a lot of open space to the left and right of the radiator, which allowed a lot of air to enter. This was necessary to cool the carburettors, which could not get too hot. But we discovered that far too much air was being let in, which accumulated under the hood and pushed the car up because it could hardly flow away through the bottom of the car, there was no good circulation. The question was, of course, how much incoming air we could block without compromising the cooling. We eventually found the answers to these questions. We closed off the openings next to the radiator and, with all kinds of refinements under the hood, we achieved a Cw of 0.4. That is what I am most proud of in the entire period that I worked on the S30Z.”

“Two months later, we received the promised calculator. It was two meters tall and 50 centimeters wide and had an IBM Computer logo on it.”

When Takeo Miyazaki climbed out of Chris Visscher's 240Z after an afternoon, he was moved and beaming. He wanted nothing to do with words of thanks for his visit to the Netherlands. “I thank you because you have brought back so many wonderful memories for me. The development of the S30 was the best time of my life. No one was involved in its development for longer than I was, but if someone asks me if I developed it, I say 'no'. It was a team effort, and every day was a pleasure and a source of joy. I regularly spent days and nights working on the car, for example when I was busy with the crosswind sensitivity. When the normal working day was over, I clocked out so as not to anger the union, and then quietly went back to work. I slept at the office. During that period I got married and once worked thirteen days and nights in a row. When I got home, all the lights were off and there was a note on the table. It was from my wife, saying she had gone back to her mother's. I went to see her right away – and luckily she came back a few days later.”

Text: Ton Roks / Photography: Luuk van Kaathoven

Takeo Miyazaki An untold and touching story

The story of this man is far more exciting than you might think. We had the honor of taking a look at his private archive and want to share his life story with Nissan with you.