I. Introduction

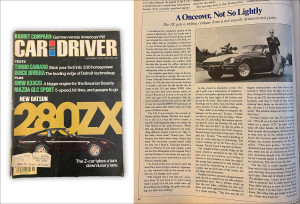

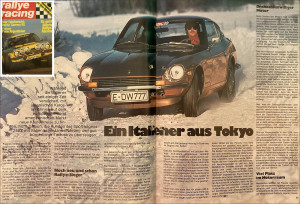

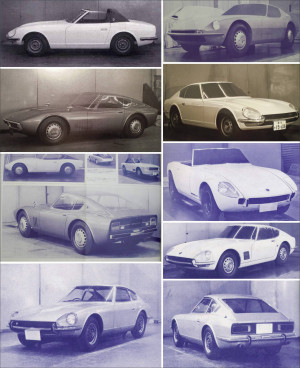

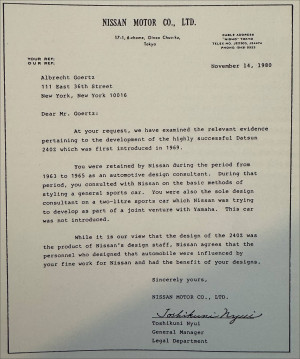

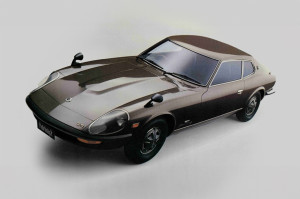

If you believe car magazines, read books or even look at international publications on the subject of Nissan or Datsun or even the Nissan Fairlady Z, Datsun 240Z or Japanese vehicles in general, then one thing quickly becomes clear: Albrecht Graf von Schlitz, known as von Goertz and von Wrisberg, provided the sketches for the design of the Datsun 240Z.

Some even say that he is the true designer of this car. Others say it was his idea. Here and there you even read that he also worked on the Porsche 911.

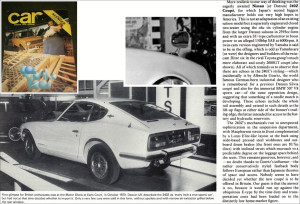

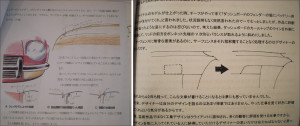

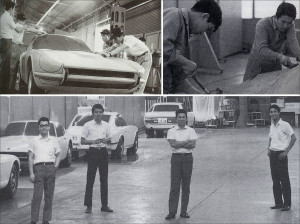

But did he? All that? No one is sure, and if you ask around a bit and read several sources, there is clearly no clear line here whether he was the designer, head of design or the designer of the Z. Somehow he seems to have been involved in everything. Alone. From America. Without speaking Japanese. Without having visited Japan and Nissan too often. And without the help of Nissan's Japanese employees. But could that really have been the case? Can he alone be responsible for the success of these cars, and who else at Nissan was involved? You read very little about KIMURA Kazuo, MATSUO Yoshihiko or ITSUKI Chiba and YOSHIDA Fumio in above all German-speaking countries.

At this point, I apologize for a very German view of this topic. But I, the author of this article, am German. And in general, it is often the Germans who attach great importance to their German count. After all, he is said to have helped Nissan to create such a successful car. But let's wait and see.

And why should they? After all, they were "only" Japanese employees of a large corporation and not blue-blooded German designers whose business cards are almost exclusively adorned with the BMW 507.

So let's embark on a journey full of contradictions, quotations and copied repetitions.

Me, Florian Steinl, Datsun enthusiast, collector of thousands of Nissan documents and early fan of the brand, is in charge of this work. Thanks are also due to Thorsten Link, German journalist, editor and presenter of many car magazines. Thanks are also due to Alan Thomas, Carl Beck, Kats Endo, Brian Long and Ian Patmore, whose tireless commitment has kept the subject of the Z alive for many decades and who have endeavored to provide facts and evidence.

Florian Steinl

Florian Steinl